Frontier Fellow - 2nd Week

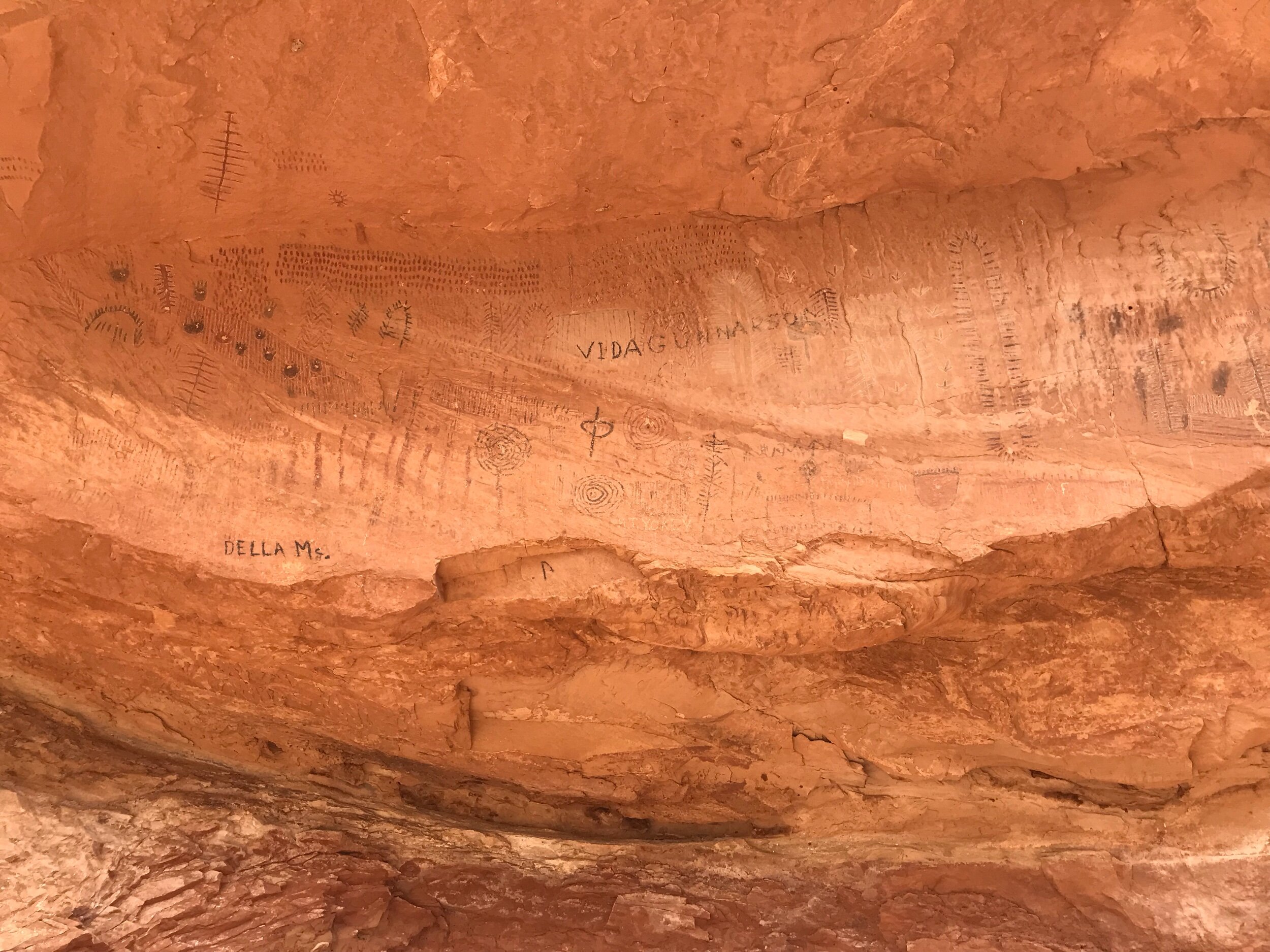

It’s incredible that drawings from ancient groups and civilizations can be seen today on rock walls, boulders and overhangs alongside those of more recent Indigenous communities. The first petroglyphs I observed in Utah were about a mile into a leisurely hike through a wash within the Rafael Swell, a trailhead 30 minutes west of my residency in Green River.

Once I managed to recover from witnessing someone jump over the cliff edge of the canyon (they were doing an adventure sport known as base jumping) I came upon the faded red pictographs of what folks have attributed to the Barrier Canyon culture. I immediately started crying, seeing these drawn figures along with the calendar system just to the right of them affirmed so many things for me. One being that there are so many ways cultures express & embody knowledge. Another, was the playfulness that I personally took away from the rock art, something that can be hard for me to lean into when creating art.

Once observed, I spent some time reflecting on some of my notes from the one academic book I brought along as part of my research at my residency, Diana Taylor’s The Archive & The Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. I have been absent on Instagram for the entirety of my road trip & residency as a way to be more grounded & present with my experience, so it was incredibly curious that the day I chose to break my absence all social media platforms owned and managed by Facebook decided to shut down for the majority of the day.

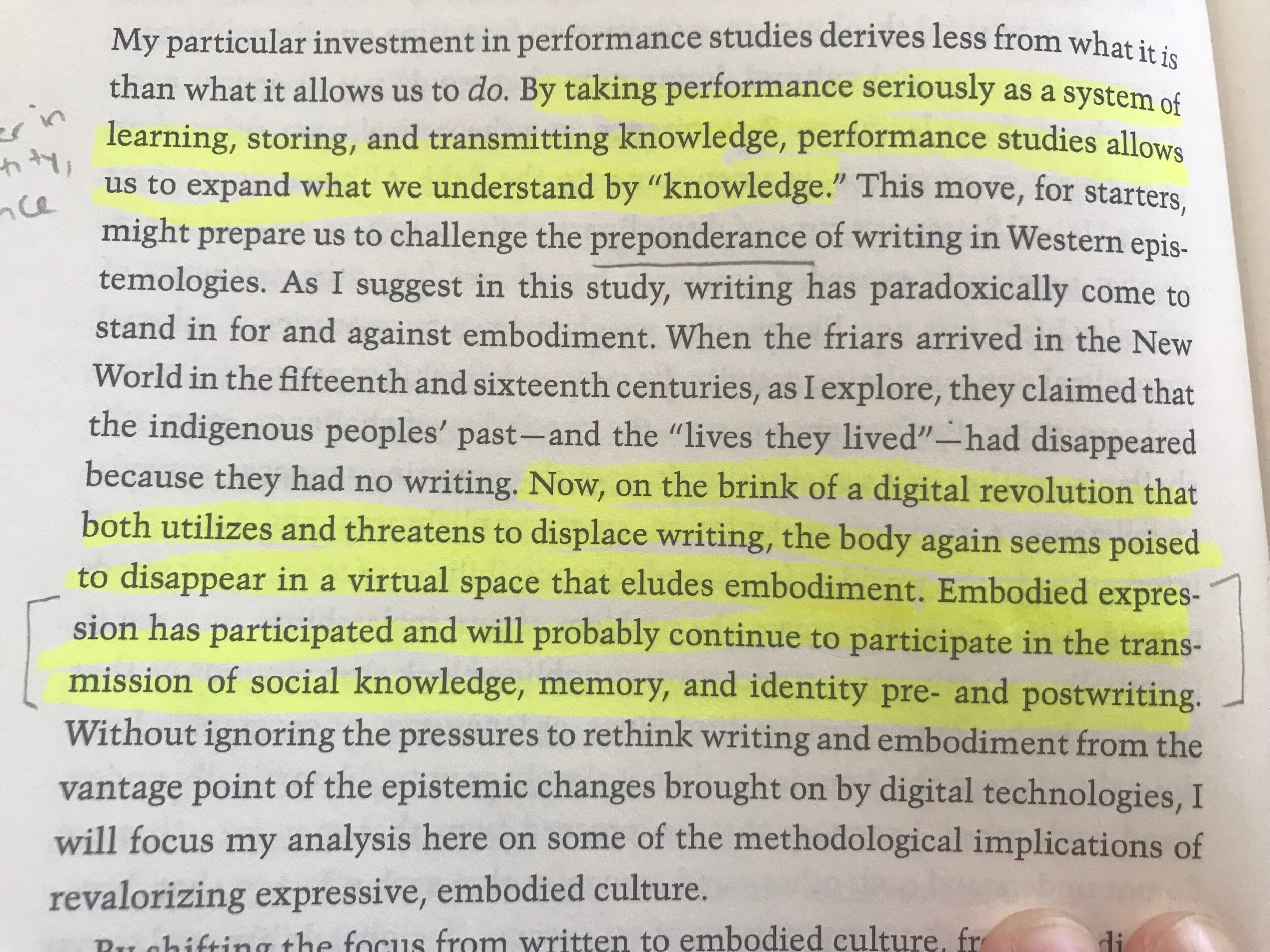

I instantly though of a recent passage in Taylor’s text, which reads as follows:

By taking performance seriously as a system of learning, storing and transmitting knowledge, performance studies allows us to expand what we understand by “knowledge.” This move, for starters, might prepare us to challenge the preponderance of writing in Western epistemologies. As I suggest in this study, writing has paradoxically come to stand in for and against embodiment. When the friars arrived in the New World in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as I explore, they claimed that the Indigenous peoples’ past—and the “lives they lived”— had disappeared because they had no writing. Now, on the brink of a digital revolution that both utilizes and threatens to displace writing, the body again seems posed to disappear in a virtual space that eludes embodiment. Embodied expression has participated and will probably continue to participate in the transmission of social knowledge, memory, and identity pre- and postwriting.

From this text, I recalled moments in which my experience was dismissed or under-minded (mostly by white cis het men) due to my knowledge being rooted in tradition, storytelling, body memory and personal happenings. If my opinion or comment could not be traced back to an academic paper, it was then seen as ignorant or void of intellect. It is my belief that due to being a product of academia, I too forget how much knowledge can be experienced, created and therefore shared with others through embodiment.